Oil policy after the Ekofisk discovery

Ekofisk was discovered virtually against all the odds. Operator Phillips Petroleum had actually sought permission to drop the final well in its drilling programme. But the US company decided to go ahead after all because it would have had to pay the government USD 1 million in any event as well as the cost of chartering the Ocean Viking drilling rig. The bit penetrated an uncontrollable gas pocket after only nine days. Since a little oil was also brought up, it was decided to drill yet another well. Few of the crew had any faith in the outcome and were getting ready to look for other jobs. But their pessimism proved unfounded.

Ekofisk also took Norway’s politicians by surprise. Although the Ministry of Industry had been notified of the discovery just before Christmas 1969, the news was not made public until Phillips issued a press release on 2 June 1970. Plenty of questions needed answering. What would the find mean for Norway? How could Norway’s interests best be protected against the powerful international oil companies in the early phase, before oil operations really got going? What oil policy should the country pursue? Should the state play an active role? And how was that to happen?

An active state

As early as the 1960s, the Storting (parliament) had made some important choices which laid the foundations for a national oil policy. These enjoyed broad political support.

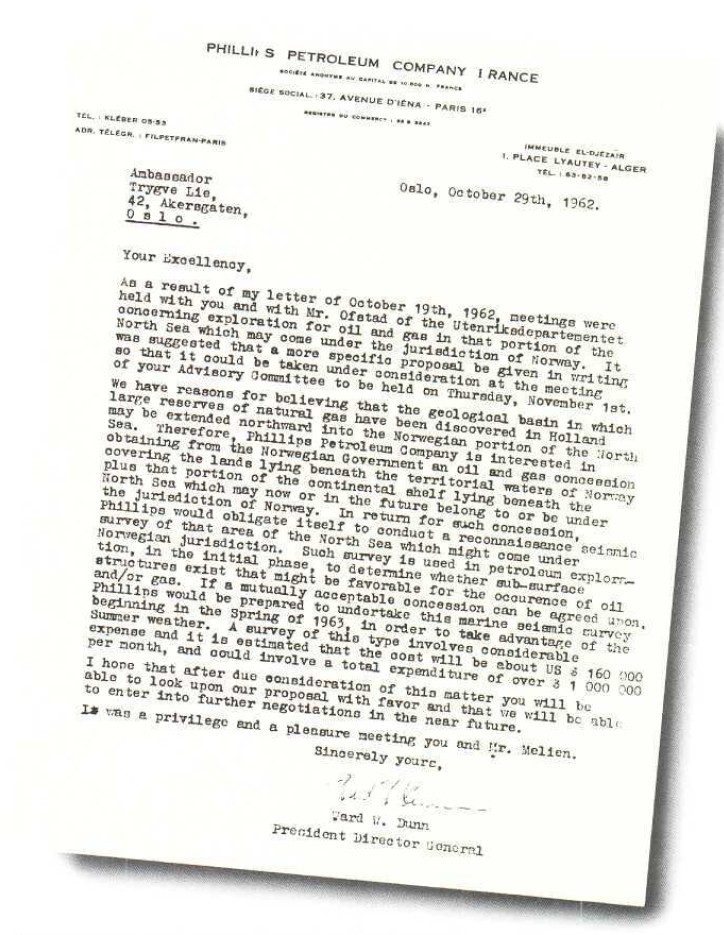

An important political step had been taken after the Norwegian government received the initial approach from Phillips in 1962 seeking rights to explore for oil and gas on the country’s continental shelf (NCS). The Storting passed an Act on 21 June 1963 which established the state’s right to submarine natural resources. This doubled Norway’s area and marked the first step in preparing for a possible oil age.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1963-06-21-12 In the same year, the government issued permits to various big multinational oil companies for conducting geomagnetic and seismic surveys on the NCS. The data they acquired formed the basis for deciding where to apply for licences.

Companies involved in the Middle East, like Esso and Shell, were used to securing ownership of the oil when they were granted a concession for an area. That was not the way the Norwegian government wanted to do things. It could draw on experience from Norway’s hydropower developments in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to avoid granting full control to powerful foreign companies.

When Norway’s first offshore licensing round was announced on 9 April 1965, it was based on regulations which built on the old hydropower concession laws. These secured the state’s rights to revenues and the ownership of the subterranean resources. Oil companies could seek permission to explore, develop and produce for a defined period. After that expired, the rights reverted to the state and the companies would have to reapply for them if necessary.

Before the first licensing round was announced, the southern part of the NCS was divided into a checkerboard of 314 blocks. The Norwegian Petroleum Council was established, with director general Jens Evensen at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as its chair, to follow up the award of acreage put on offer.

The Ministry of Industry initially awarded 78 production licences to eight individual or group applicants. Recipients included some of the world’s largest oil companies, such as Esso, Shell and Amoco. Phillips Petroleum, which had been the first to show an interest, secured blocks together with Fina and Agip as the Phillips group. Norway’s Norsk Hydro participated in the Petronord group with seven French partners, while Norwegian company Noco acquired licences alongside Amoco in the Amoco-Noco group.

In order to administer the growing level of activity, the industry ministry established a separate oil office in 1966. This was initially only a temporary creation, in case nothing was found on the NCS. Esso became the first to “spud” (start drilling) a well in the seabed during July 1966, and the first to discover traces of oil in what later became known as the Balder field. Phillips struck oil in the Cod field in 1968. But these discoveries were small, and so many “dry” wells were being drilled that the oil companies began to lose faith in the NCS. Several of them began closing their offices and sending people home in the spring of 1969.

Nevertheless, continued hopes of finding oil meant the government had to be prepared for that eventuality. If commercial quantities of oil were discovered, “staffing of the [oil] office must be substantially strengthened”, White Paper no 95 for 1969-70 stated. “In that case, it could be relevant to establish a separate directorate for continental shelf issues, possibly also a state oil company to handle the government’s commercial interests in petroleum production.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 95 to the Storting for 1969-70. That resembled a plan.

These words suddenly became relevant. No sooner had the White Paper been submitted than oil was discovered in Ekofisk.[REMOVE]Fotnote: https://ekofisk.industriminne.no/en/home/ Engineer Olav K Christiansen in the industry ministry’s oil office was notified of the find on 23 December 1969, and he and his small band of colleagues had their hands full the following spring.

Instead of being concerned about which oil companies were going to pull out, the office received a string of requests for consent to drill more wells. The result was great activity and several more discoveries.

Conservative Party politician Sverre Walter Rostoft was industry minister at the time in the non-socialist coalition led by Per Borten from the Centre Party. He told the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) on 9 September 1970 that oil “may mean a very great deal, it could actually initiate a completely new era for Norway. […] We must expect new discoveries. […] That will create some new companies, but first and foremost provide work for existing industry.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: NRK schools broadcasting, 9 September 1970.

The industry ministry initiated a number of studies on bringing the oil and gas ashore in Norway and on safety provisions. Since oil production was soon due to begin, a commission chaired by engineer Knud-Endre Knudsen, and named after him, was appointed to come up with proposals for organising state involvement both inside and outside the ministry.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Innstillinger og betenkninger fra kongelige og parlamentariske kommisjoner, departementale komitéer m.m., 1971, Nr. 3.

Parliamentary focus on Norwegian oil

Rostoft spelt out the non-socialist government’s view on oil policy when the Storting debated the Speech from the Throne on 20 October 1970:

At the moment, we still know far too little about how large these [oil] resources actually are. What we do know, however, is that billions of kroner will be required over the next few years to clarify this and that, even with spending billions, it might be a washout. We must bear this in mind when drawing up a national oil policy. […] The North Sea oil is making its entry to everyday Norwegian life, with the joys and sorrows, the opportunities and the worries which this brings with it.

Despite Ekofisk, Rostoft was uncertain about the whole oil project. He felt landing production from this discovery and possible others in Norway was not necessary at any cost. He appeared a little relaxed with regard to the state’s role. As industry minister, for example, he wanted to propose the creation of a state-owned company which would have sole rights to seismic surveying on the NCS above the 62nd parallel (the northern limit of the North Sea), but it was not urgent. As mentioned above, the Knudsen commission was considering the future organisation for handling the “oil problems”. Only when this study had been completed in six months time could the government take a final decision of the organisation of state involvement.

The opposition parties in the Storting were far less patient. Ingvald Ulveseth, Rolf Hellem and Trygve Bratteli from the Labour Party all spoke during the Speech from the Throne debate, and were very much in agreement with each other on oil policy. As parliamentary leader of his party, Bratteli’s contribution can be taken as representative for its standpoints. In his view, the Ekofisk discovery showed that Norway was facing a new industrial activity of considerable scope. The government had a big responsibility to protect the interests of Norwegian society. It was essential to build domestic expertise in the meeting with the foreign oil companies. Unlike Rostoft, Bratteli made it crystal-clear that production from the NCS should be landed in Norway. To meet the challenges posed by the new industry, he concluded:

We would propose that preparations are made as soon as possible for a national oil company, preferably state-owned or possibly in a partnership where the state holds 51 per cent of the share capital. Such a company must be able to conduct exploration for as well as production and exploitation of Norwegian deposits.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Proceedings of the Storting 1970-71: 203. Storting debates (bound edn), vol 115 no 7a.

Ulveseth agreed fully with Bratteli where a national oil company was concerned, and also wanted a petroleum directorate:

We also believe that securing full national control of exploration and production in the Norwegian sector of the continental shelf must be a key task. That makes it necessary to strengthen and expand the central administration, possible through the establishment of a separate petroleum directorate.

Hellem’s speech was both forward-looking and internationally oriented. He pointed out that the state in both Italy and France had become involved through state companies in exploration for and production of oil, and exercised control over the activities of the international oil companies. That contrasted with the USA, where privately owned oil companies continued to play an important role in domestic politics. In principle, Hellem believed that the oil and gas resources were the collective property of the Norwegian people, which could best be administered by establishing a state oil company and landing production from the NCS in Norway:

This should be the guarantee of an administration of the people’s collective assets which can best benefit society as a whole. Collecting fees and taxes is not enough.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Storting debates (bound edn), vol 115 no 7a.

Ensuring that the oil wealth benefited society as a whole was to be a constant refrain during oil-related debates in the Storting over the coming years.

Johnsen and oil policy

Formulations in Hellem’s speech during the Speech from the Throne debate have much in common with a memorandum prepared by Arve Johnsen, chair of Labour’s industry policy committee and later the first CEO of Statoil. Johnsen was familiar with the refining and processing oil products from his time at Hydro. When the Ekofisk discovery became known, he believed the Norwegian government had to exploit the industrial potential offered by offshore production, and not rest content with simply collecting taxes. In his view, the oil had to be landed in Norway. That would create the basis for petrochemical industry and for regional development through base construction and equipment deliveries. Johnsen was also concerned with what the oil could mean “for the power relationships in the business community” – in other words, the balance of power between private- and public-sector enterprises in Norway and the relationship between Norwegian and international oil companies.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, Nerheim, G., & Norsk petroleumsforening. (1992). Fra vantro til overmot? (Vol. 1, p. 523). Leseselskapet., 1992: 163.

The opinions he had expressed at an early stage appeared to be shared by leading industry-policy spokespeople in the Labour Party.

Borten’s plans

What views Borten, who was prime minister from 1965 to 1971, held about oil policy found no expression in the Speech from the Throne debate. However, that did not mean he had intended to do nothing.

As mentioned above, Rostoft had appointed the Knudsen commission to propose how the state should organise itself in its meeting with the oil industry. Borten himself planned to use Hydro as the government’s instrument in this field. But this intention was kept secret and pursued behind closed doors.